Challenges & Design Decisions

Deciding On a Model

Section titled “Deciding On a Model”

Embeddings are the central mechanism for similarity search, so finding a

suitable embedding model was essential. We originally started with

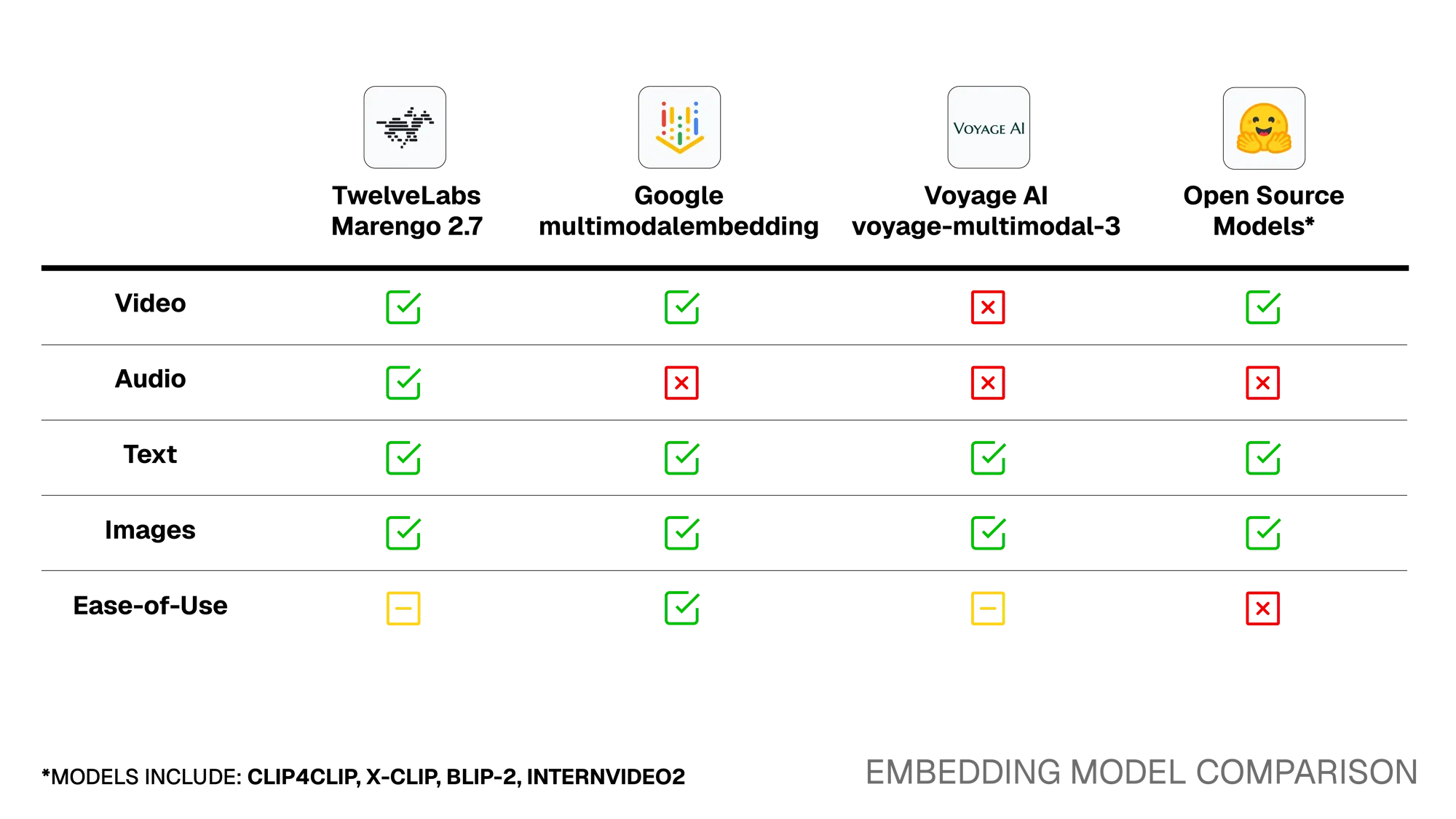

voyage-multimodal-3, which only has native support for image and text modalities.

We chunked content into segments, extracted frames and audio transcriptions,

then embedded those components. This approach captured both visual and speech

modalities, but lost significant meaning since frames are extracted at intervals

and only spoken text is captured from the audio.

Looking for better embedding quality, we explored open source options including embedding models like CLIP4CLIP and X-CLIP as well as feature-extraction from vision-language models like BLIP-2 and InternVideo2. While we successfully generated video embeddings using these models, we were concerned about introducing complexity in deployment, since we would need to manage the model weights and GPU compute ourselves.

We then evaluated Google’s multimodalembedding@001 and TwelveLabs’

Marengo 2.7. Beyond supporting longer text queries, Marengo 2.7’s key

advantage was native audio embedding support. This was crucial because we wanted

to handle audio through embeddings rather than transcriptions. Without native

audio support, we would have needed a separate audio embedding model and

parallel ingestion pipelines.

The trade-off with Marengo 2.7 is that TwelveLabs only provides an

asynchronous API for video embeddings. They do not yet provide a webhook for

completed embeddings, so users must poll repeatedly to check whether their

embeddings are completed, which can be inefficient. We found these trade-offs

acceptable and we discuss how we dealt with them below.

Adopting Serverless

Section titled “Adopting Serverless”One key take-away from the model explorations was that this space is moving quickly - we expect newer, more capable models to surface in the future. As our attention turned to architecture, we didn’t want to design a system that was tightly coupled to the model; swapping should require minimal updates instead of an entire rewrite.

Our first working prototype was a monolithic local Flask app, which was a proof of concept and helped us identify how we could separate concerns in future iterations. For production, we chose a serverless architecture as it separates concerns and scales to match usage. The ingestion and search pipelines both use event-driven workers, with embedding requests flowing through both producer and consumer functions so the model stays isolated. Additionally, this approach is more cost-efficient as end users wouldn’t incur idle infrastructure costs.

However, serverless came with trade-offs. Beyond cold start latency, we faced execution time limits, memory constraints, and reduced debugging visibility compared to long-running instances. We also needed to handle cases where embedding tasks might exceed function timeouts. These trade-offs were acceptable for the type of applications we were targeting, and we discuss some of our solutions in the following section.

Asynchronous Processing with SQS

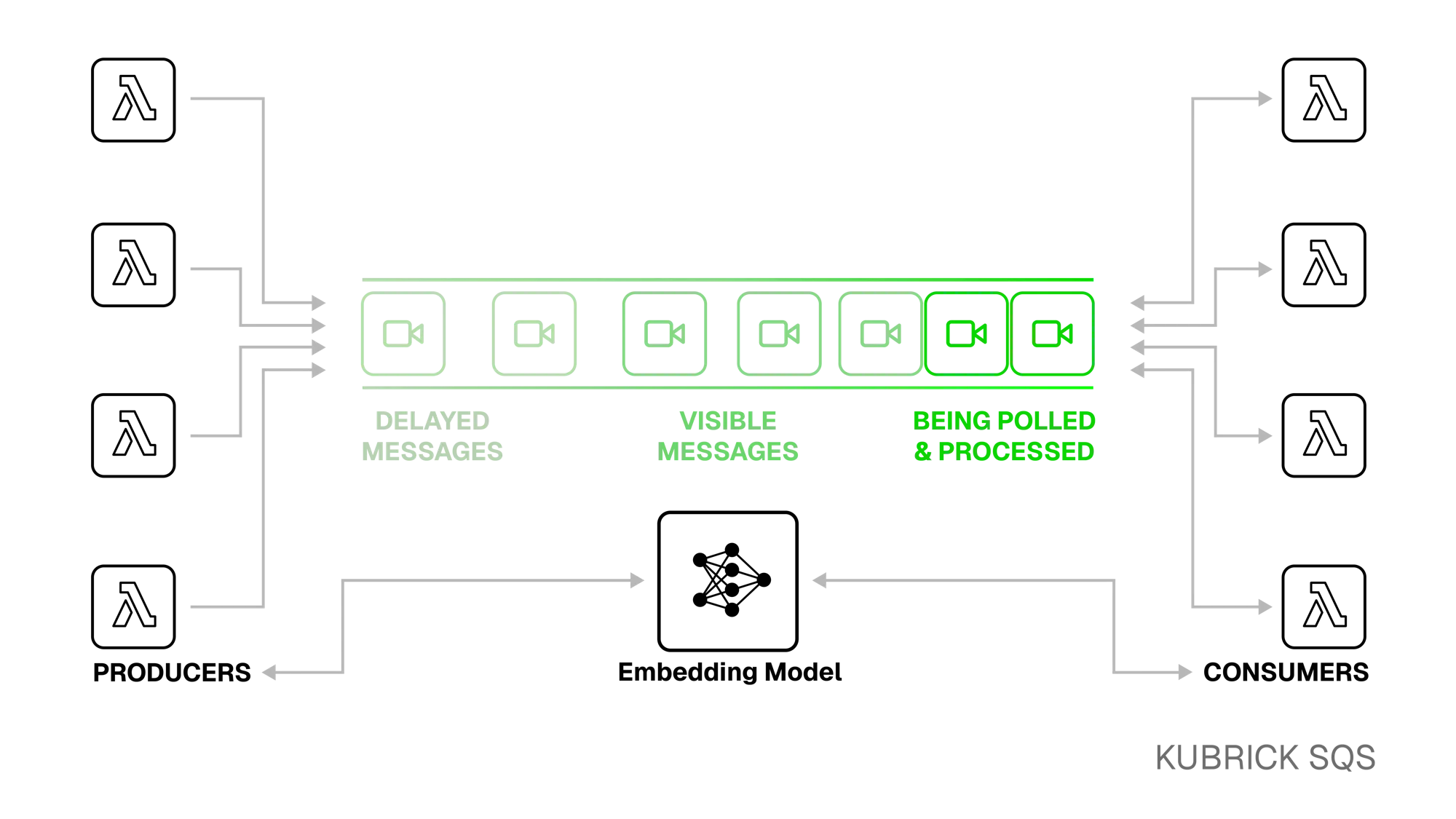

Section titled “Asynchronous Processing with SQS”One issue with embedding video is that it is much slower than embedding text or a single image. As mentioned above, TwelveLabs handles this by providing a separate asynchronous API for video embeddings, but they do not provide a notification mechanism through something like a webhook. This was not an issue on our local server prototype, since we could just poll the TwelveLabs API until the embedding was ready.

However, as we migrated to a serverless architecture, we realised that having one Lambda function handle the entire embedding process was problematic. Keeping Lambdas running continuously while waiting for the video embedding to be ready would incur unnecessary costs, create a dependency on TwelveLabs, and potentially cause issues due to Lambda lifetime limits.

To solve this, we considered AWS Step Functions for polling, but their pricing penalizes long waits and the state machine overhead felt excessive for a simple “check and retry.” Redis was another option, but it would have required provisioning, managing, and polling a separate service. In the end, we landed on Amazon SQS as the simplest solution, since it is managed, scales well, and integrates natively with AWS Lambda functions.

The queue acts as a buffer for in-progress embedding jobs, preventing idle and long-running Lambdas. Producers handle delivering the video to the embedding model, and Consumers handle retrieving the embedding. If the embedding is not yet available, the consumer Lambda simply pushes the message back into the queue to be retried later.

The trade-off is a slight increase in code-complexity - the consumer Lambda, for example, has to explicitly and idempotently manage SQS visibility timeouts and return pending messages to the queue.

Unified Storage with RDS

Section titled “Unified Storage with RDS”For storing the embeddings, we first looked at managed vector databases like Pinecone and Chroma. Using a managed service to store and retrieve our vector embeddings would have allowed us to abstract away a lot of our database insertion and querying logic.

The downside is that these services are primarily designed to store vectors,

which means that we would have to maintain a separate relational database to

handle our other non-vector data like video metadata (videos) and our

embedding tasks (tasks). Ingestion and search queries would then have to

manage and synchronise data across two separate databases, increasing latency

and adding points of failure.

To avoid this, we decided to use PostgreSQL RDS with pgvector. This gives us

both vector search and relational queries in one schema, supporting atomic

writes and eliminating cross-service glue. RDS also provides managed backups,

failover, and IAM-based access control, without another external SaaS

dependency. Smaller teams deploying with Kubrick are also much more likely to be

comfortable with SQL, which was important because we wanted to ensure that

Kubrick was easy to extend and build on.

One challenge was schema initialization. AWS does not have a native feature to populate a newly provisioned database with a schema. To handle this, we built a “DB Bootstrap” Lambda which is triggered by our automated deployment process to create the necessary tables, extensions, and indexes.

Optimizing Latency

Section titled “Optimizing Latency”Calling AWS API asynchronously

Section titled “Calling AWS API asynchronously”After we deployed the first version of our architecture on AWS, we noticed that

response latency for our /videos and /search API endpoints was higher than

we would expect - this was concerning because these endpoints are the ones that

most impact user experience. We investigated the logs and determined that the

bottleneck was the process of generating presigned URLs for temporary S3 access.

For example, the API endpoint handler for the /videos endpoint was calling the

AWS S3 API to generate presigned URLs for each video object in the response.

Since the AWS python SDK does not provide a way to call this function

asynchronously, the latency of the response was scaling linearly with the number

of videos requested. We rewrote the Lambda layer handling S3 operations to call

the S3 API asynchronously using threads, which significantly improved response

latency.

Optimizing the Database

Section titled “Optimizing the Database”

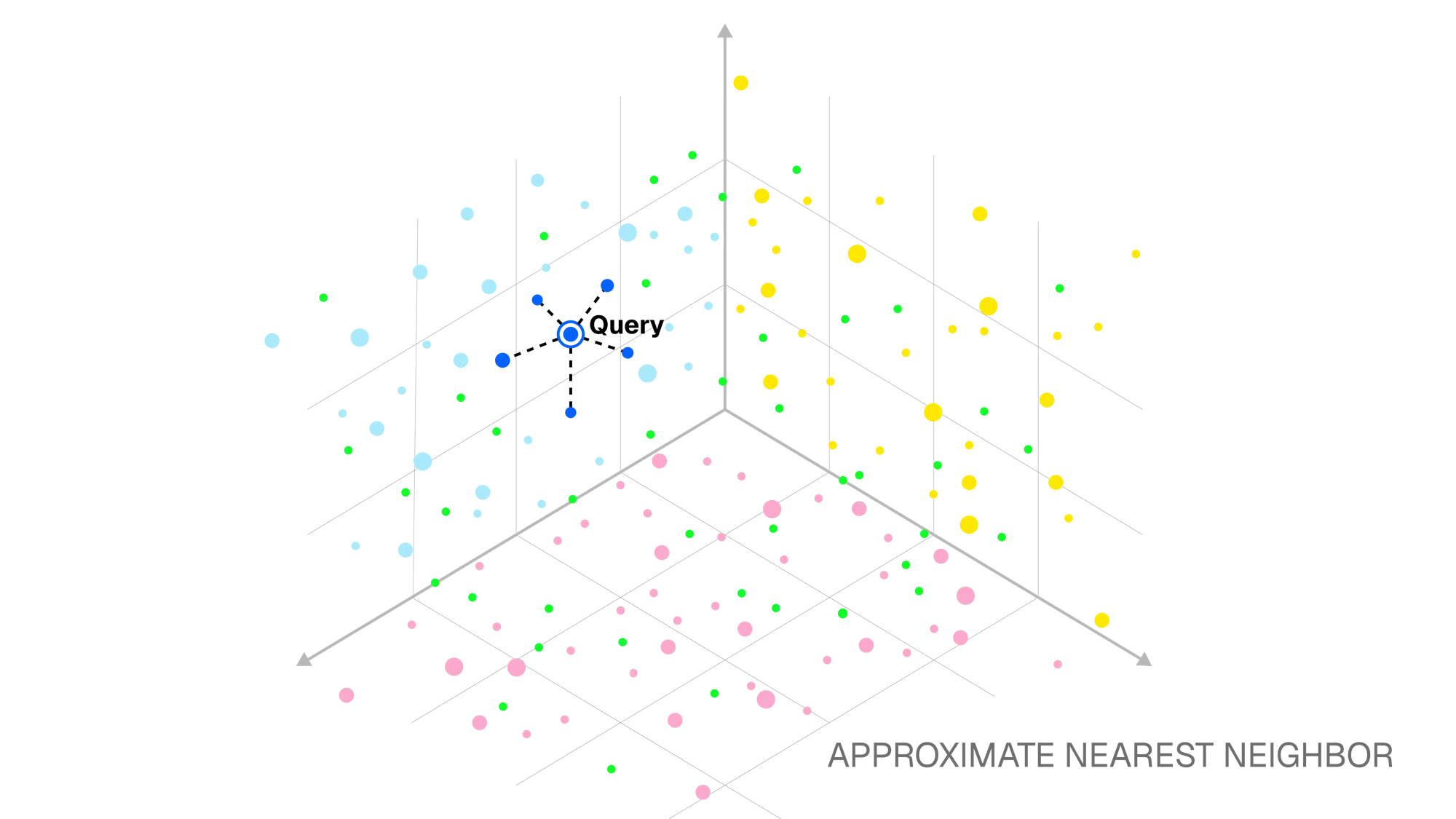

By default, pgvector performs exact nearest neighbor search, which returns

perfectly accurate results. However, this algorithm scales poorly because it

compares the query embedding with each embedding in the database table. Because

we wanted to ensure that Kubrick’s search remained fast at scale, we decided to

switch to Approximate Nearest Neighbour (ANN) search using the Hierarchical

Navigable Small World (HNSW) algorithm.

This means that instead of comparing our query with each embedding in the database, we now maintain a graph (as a PSQL index) that our algorithm traverses greedily to find the most similar set of embeddings. This reduces search time dramatically for larger datasets, but the trade-off is that insertion is slower and results are no longer “perfect”, so some relevant matches may be missed. Given that search query latency impacts user experience much more than ingestion time, and that recall performance with ANN was still very high, we found these trade-offs acceptable.

Minimizing Redundant Embedding Requests

Section titled “Minimizing Redundant Embedding Requests”We found that the biggest bottleneck for search request latency was the time spent waiting for the embedding model to process the search query. For media queries, which tend to have heavier payloads, the round-trip time (RTT) of the request could easily exceed 10s.

To address this, we added a read-through cache layer deployed on DynamoDB. We

chose DynamoDB over Elasticache because the performance benefits of the latter

(<10ms vs <1ms) were relatively small compared to the latency of a

cache-miss (>1000ms). Search request parameters are used as the cache-key, to

look-up and store vector embeddings returned from the external embedding model.

We found that the caching layer significantly decreased latency for repeated queries, helping with use cases like content recommendation where media queries are common and cache hits are likely. Though the read-through caching strategy is not as latency-efficient as write-behind, it allows us to decouple the caching layer from the rest of the architecture so that users can easily disable the cache according to their use case.